A coule of weeks ago I was surprised to see the amount of fan fare surrounding the 10th anniversary of Mean Girls, the 2004 Tina Fey scripted cult teen movie classic which combined sharp, witty dialogue and a clever variation on a Heathers-like narrative with some stellar comedic performances from the likes of Fey and Amy Pohler and (what were then) up and coming stars Lindsay Lohan and Rachel McAdams. It seemed that Mean Girls was everywhere. Prolific feminist sites such as Jezebel ran articles that listed the characters in the film from worst to best, while social media site BuzzFeed went crazy with articles on fun facts about the film and some obligatory quizzes. Even academic journal site JSTOR paid tribute to the film with an image from it plastered on its homepage.

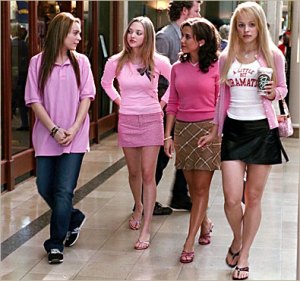

For those who don’t remember the film (or just happened not to have seen it), here’s the plot in a nutshell. Wide-eyed teen Kady Heron ( Lohan) returns home to the USA with her zoologist parents after a 12 year research trip in Africa (as with many American films, this one is not exactly clear on which part of the continent it’s referring to). Upon her arrival in Evanston, Illinois Kady is bounced out of the home schooling system she has known for most of her life, and straight into the torturous world of the public high school. On her first day Kady makes friends with two misfits, Janis Ian (Lizzy Caplan) and and Damian (Daniel Franzense), both of who have an ax to grind with Regina George (McAdams), the school’s queen bee and the leader of the appropriately named The Plastics, the most prestigious female clique in the school. When Regina takes an unusual interest in Kady, Janis and Damian draw her into their plan to take revenge against Regina and the Plastics. As part of this presumably ingenious plan, Kady joins The Plastics as the group’s fourth member, instigating conflict between Regina and fellow Plastics, insecure airhead Gretchen Wieners (Party of Five‘s Lacey Chabert) and bimbo Karen Smith (Amanda Seyfried, making her film debut) who believes her breasts have the power to provide weather forecasts. The plan hits a snag, however, when Kady becomes completely integrated into The Plastic lifestyle and, in doing so, realizes the appeal of being Regina George, more specifically one of the “mean girls” referred to in the title.

Now don’t get me wrong, Mean Girls is a fun film. I’ve watched it a couple of times since it was first released and it’s actually remained quite fresh since 2004. It’s still endearingly funny, even quite touching and, despite its ignorance towards Africa and its geography, I always enjoy Kady’s mother’s off-hand reference to Ladysmith Black Mambazo when it pops up. However, as enjoyable as it is and as catchy some of its lines of dialogue are ( Gretchen’s enthusiastic outburst of “that’s so fetch” is a quirky gem), I just don’t see Mean Girls as a film that screams for or even deserves a monumental media profile to celebrate its 10th year of existence in the pop culture stratosphere. Within the wider context of its genre, the film is hardly revolutionary. A decade before its release Amy Heckerling’s Clueless had a finer formula in place, blending together a contemporary reworking of Jane Austen’s Emma with a multitude of print, film and music texts both from the nineties and other decades gone by. That film also created a vocabulary that extended beyond “fetch” to incorporate a whole dictionary of new linguistic terms such as “whatever” and “jeepin'”, many of which remain within the epic tome of urban slang to this day. Years earlier the aforementioned Heathers, the film Mean Girls has most frequently been compared to, conceived the template for the high school satire. Of those two films, Clueless has managed to find a footing within 21st century culture, often getting referenced on social media sites in some form or another and appearing in a number of academic critiques of film adaptations of Austen’s work. Yet, it’s unlikely that when it reaches its 20th anniversary next year, it will get a “shout out” on a JSTOR homepage.

I guess, within a 21st century context, it’s clear exactly why Mean Girls sticks out above its contemporaries. Firstly, the involvement of Fey and Pohler in the film implies that it’s commercial comedy gold. At present, Fey and Pohler are the “it” girls (or rather “it” women) of the commercial comedy scene. Regardless of whether she has 30 Rock in her life, Fey has perfected a signature comedic performance style that has captured the public imagination, particularly in terms of the way it plays on both the independence and neuroses of the 21st century working professional. Pohler’s performance style, most notably in Parks and Recreation, works to a similar effect and when the two women are put together in one room (as the past Golden Globes ceremony indicates) they create comedic dynamite. The film’s other potentially attractive quality for 21st century audiences sadly relates not to its artistic merits, but rather to the reputation of its star, the tragic Miss Lohan. Mean Girls was produced quite soon after Lohan first established herself as a rising teen star in Freaky Friday, a period where she was actually appreciated for having some worthwhile acting chops, rather than for what tabloid fodder she was capable of producing. From this perspective, watching Mean Girls is in some sense a tragic tribute to the Lohan that was and the Lohan that could have been had a history of addiction not completely derailed her career and turned her into a celebrity joke as opposed to a movie star. It’s in fact in Mean Girls where Lohan is at her most likable, portraying Kady as a shy and awkward teen who just happens to fall in with the wrong crowd but then redeems herself by emerging as a self-assured and kind young woman. The kind of transformative process that Kady undergoes in the film is similar to the one fans wish Lohan would undergo in reality. The film, therefore, inadvertently provides a medium through which this process can be experienced However, when detaching Mean Girls from both these draw cards, what is left is a film which is simply “nice”. More specifically, it’s a film with nice performances, nice jokes and nice production values. “Nice” implies a film that still makes for a pleasant viewing when it’s broadcast on TV for the umpteenth time, but hardly one that should, in fact, be immortalized.

Perhaps my main (read real) issue with Mean Girls is that it doesn’t, in fact, follow through with what could have made it revolutionary. Here I have to refer to the film’s ending which again is “nice” and sentimental but also very much in line with the standard ending of every second tween movie that’s made it onto the Disney Channel. Fey positions Kady as a type of teen savior who, by admitting her own flaws and making a crowd-pleasing speech at a prom, is able to unite her class and end the reign of bitchiness at her school. It’s a pleasant conclusion but it’s not exactly authentic. Anyone who’s ever been to high school knows that bitch warfare is an unfortunate part of the high school experience. In fact, high school isn’t high school without it and the notion that it can be eliminated is problematic and misguided. For me, the film should have ended with a redeemed Kady but the original status quo still in tact, one where cliques still exist and Regina George still terrorizes (or is that “bitches”?) the shit out of people. Perhaps to give this somewhat more cynical ending a more satisfying twist, the film could flash forward to a couple of years later where Kady, following in her parents footsteps, becomes an award winning zoologist and Regina, following in her mother’s footsteps, becomes a rich housewife who rather pathetically indulges in botox and attempts to relive her youth vicariously through her teenage daughter, otherwise known as Regina Jr. Perhaps Fey could have channeled a variation on JK Rowling’s ending to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (minus the “all was well” part) in the sense that she could have scripted a scene where Kady and Regina drop their teen daughters off at the same high school, engaging with one another in a way that suggests that the power struggle will go on, more specifically between their two daughters. The bottom line is that, for most of its running time, Mean Girls is an edgy satire and this where the appeal of its narrative lies. To soften that satire by having a “nice” ending, suggesting that hierarchies can be dismantled and a utopian vision of high school can be realized, seems like just a tad bit of a cop-out on Fey’s behalf, as well as rather generic.

Maybe one day when I inevitably end up watching the stage musical adaptation of Mean Girls (yes indeed it is happening) out of curiosity, I’ll gain a new-found appreciation for this “nice” ending and maybe even the film as a whole. Until then though I’m left to wonder why exactly we’re celebrating this film’s tenth anniversary. Is Mean Girls seriously that “fetch”?

Source for Image 1: http://movies.msn.com/movies/gallery.aspx?gallery=4355&photo=5210fda2-fa8d-4fca-84a5-019cfc3ae1d8

Source for Image 2: http://www.journeytothecenteroffashion.com/fashion-in-film-mean-girls/